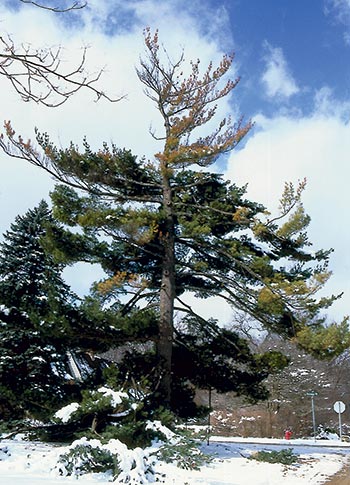

Many people in Michigan have noticed the yellowing and thin appearance of white pines that have stood sentinel and provided shade for decades. Some who didn’t recognize those earlier symptoms will see the first sign of this region-wide white pine problem as a dead tree.

What horticultural professionals have noticed in the Midwest, including southern lower Michigan and some areas further north on the mitten, is best described as white pine decline.

Decline is reduced vigor, below-normal functioning and slower growth in a tree when those symptoms can’t be attributed to a specific disease or insect. Trees in decline may fall prey to insect or disease problems because they are weak, but those are additional complications rather than causes of decline.

A tree may decline for many years. If its situation doesn’t improve, it may exhaust its lifetime starch reserves and begin to exhibit dieback—which looks just like it sounds and often ends in death.

I first noticed white pine decline in the mid 1990s. Many white pines yellowed suddenly, alarmingly and at least one 40-year-old tree on a property I garden died. Based on the positions of the most afflicted trees relative to northwest winds and open ground, and a severe winter that had just passed, I attributed the problems to cold-related root damage. Others came to the same conclusion and experience since then seems to support this.

Do you remember February, 1996? The white pines do! On the night of February 2-3, temperatures from the Great Plains to New England dropped to lows never seen before or not seen for 40 years. That week, the outbreak of Arctic air set nearly 400 record daily minimums and at least 15 all-time lows in the eastern U.S. Wind chills of -50 and -100 degrees were common.

In southeast Michigan, the mercury plummeted 15 to 20 degrees in just a few hours on a night when there was not even a trace of snow to insulate the soil. Branches and trunks of some plants died, and the frost knifing suddenly and deeply into the unprotected soil killed roots even on hardy, established plants.

By spring, gardeners would be mourning the loss or severe damage of thousands of decades-old Japanese maples, and finding privet hedges, rose of Sharon shrubs and even stalwarts such as old junipers dead or killed to the ground. Plants hurt but not killed would begin the slow process of regenerating roots and limbs only to be socked with drought years, one after another.

Shallow-rooted plants like white pine may have been worst hit. Left with fewer roots than they should have, they were not likely to take up enough water and nutrients to fuel regrowth. They were in trouble even if drought had not begun to compound the loss.

Six years later, my tally sheet of all the white pines I see regularly in my travels and those I tend reads this way: Some of the first-affected died and many are still struggling. Some which did not initially show symptoms developed them during subsequent drought years. Only a few recovered. Very few escaped all damage.

In its bulletin, “Decline of White Pine in Indiana,” Purdue University Cooperative Extension reported, “white pine decline… has been a problem for many landscapes in Indiana. …Declining trees usually look a pale green, or even yellowish, compared to healthy trees. Needles are often shorter than normal; sometimes the tips of needles turn brown. Needles from a previous season often drop prematurely, giving the tree a tufted appearance.

“With loss of needles, the tree has a reduced ability to produce the energy it needs to survive…

“With severe or compounding stress factors, the tree may gradually decline and eventually die. Decline may be gradual or rapid, depending on the number and severity of stress factors.”

University of Missouri Extension made similar reports like this one from August, 1999: “We have received many white pine samples into the Extension Plant Diagnostic Clinic this year… from mature white pines, about 20 to 30 years old that are in a state of decline. …Other Midwestern clinics have also seen (this) and have been unable to explain most cases of decline…”

“We therefore believe… that the problems we are seeing with white pine may be related to environmental factors and site conditions… such as heat, stress, drought, flooding and sudden extremes in temperature and moisture.”

Note that experts don’t lay full blame on the cold but on a combination of causes. Ironically, reliable cold and snowier winters may have worked in some trees’ favor.

Missouri, Indiana, Ohio and the southeasternmost part of Michigan, which have all seen many white pine problems since the 1996 freeze and subsequent droughts, are south of white pine’s native range. Since a species’ native range is delineated at least in part by climate, we know that something about the weather in our area is probably not optimal for white pine. A record-breaking warm-up that came after the 1996 cold snap may be one of the climatological events these trees can’t handle. Two weeks after the freeze, all across the area affected by decline, temperatures jumped into the 70s, 80s and 90s. For the most part, white pines growing where there was the usual reliable snow-cover or where the warmest air didn’t reach, fared better.

What happened to the white pines was outside current experience, on a scale so broad that few had the perspective to be able to recognize it. Now that we look back and know how long a tree has been declining which we just noticed this year, we can wish we knew more earlier, but it won’t get us anywhere.

So if you have a troubled white pine, have it inspected by an arborist. Rule out disease and insect problems. Give it the help it needs to fight any secondary problems. Do what you can to alleviate underlying stresses.

Establish a regular watering routine and fertilize the tree in early spring to see if it responds. Aerate the soil if it’s compacted. Be pleased if the tree reacts positively, but be realistic about its chances and your needs. Many of these trees are years past their point of no return. Even those which respond positively to treatment may take many years to recover.

Article by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.