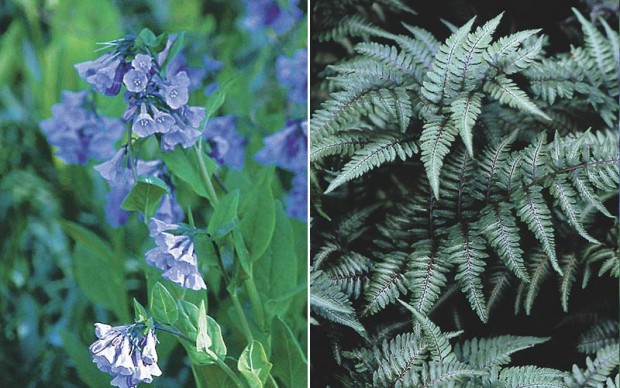

Pair perennials properly to create superb companion plantings

Doubling up on perennials. It’s the designer’s color-hungry attempt to copy and even improve on nature. Nature, which blankets the ground below trees with spring ephemerals and populates a prairie with low-growing vernal species among taller, later-blooming types. In both instances two perennial groups co-exist harmoniously. The spring species live fast and finish their business as the summer crowd takes over. The summer species graciously shed their leaves or topple to the ground at year’s end, letting in light to fuel the next cycle.

The designer who doubles up perennials will plant two species where one might be expected to fit, pairing them in one of several ways:

A) Larks with owls: One species that starts and finishes early in the season with another that comes on later. Larks often have a summer dormancy, or don’t suffer when the gardener cuts them back hard early, to make room for the owl.

B) Layered species: One wide, ground floor occupant below a narrow high-riser.

C) Equitable competitors: A shallow root scrambler with a deep or tap root, each drawing on different levels for water and nutrients, and the scrambler able to move out of the way as the other grows.

The concept is simple. Yet it is an attempt to copy natural elegance so it requires observation, patient trial and a certain ingenuity in execution. I coined the phrase “doubling up” for my garden design classes. So here are some successful doubles and the most important practical lessons I’ve learned along the way.

Be a matchmaker.

In the accompanying chart are species for doubling up, each with its qualifications listed – lark, owl, ground floor, high riser, tap root or shallow-rooted scrambler. Any species that rates a check in the “lark” column (A1) is a suitable candidate for pairing with an “owl” (A2). High risers (B1) can double up with any ground floor specialist (B2). Tap roots (C1) are right to be teamed up with shallow root scramblers (C2).

Always plan for “Right Plant, Right Place.”

In making these pairings, I leave it to you to familiarize yourself with a species’ cultural requirements—amount of sun, moisture needs and soil preference. I trust you’ve already learned the lesson that it only pays to plant where you know the species will thrive, so you’ll pair off plants only if you know they both suit the site, or you’ll modify the site. For instance, oriental poppy, a lark, can share space beautifully with the owl, hardy hibiscus, but only if you can meet the former’s need for deep, well-drained soil, plus keep that soil moist enough to satisfy hibiscus, a native of damp pond edges.

Aim for more than one qualifier.

Plants get along in crowded quarters even better if they have compatible adaptive characteristics from two or even three of the categories. For example, balloon flower as a high riser does well with ground floor rock cress. You will learn to recognize the match is more sure when you see that it also pairs a tap-rooted owl (balloon flower) with a shallow-rooted free ranging species that does its growing in late winter (evergreens have that advantage!) and early spring.

I might also pair balloon flower with hybrid pinks for the high rise/ground floor match, but I’d be less confident of success. Neither is shallow-rooted so they will compete with each other more than is good. Also, because the pinks can’t scramble—i.e. move readily by surface-rooting stems into better space when conditions such as shade from a growing partner becomes greater in one spot than another—it will be a bit slow to react to openings in the balloon flower’s “canopy,” suffer more thin spots, and be less vigorous overall.

Wait to see who wins.

Yet you should keep an open mind as you pair the plants and avoid making snap judgments once you’re growing the doubled-up combination. Some pairings will test your determination, requiring the patient trial I mentioned earlier. I call this period “see who wins” even though what I always hope for is a long-term balance of power.

When one plant is slower growing than the other, but persistent enough to endure, it’s all a matter of time. Tap-rooted, high riser gas plant increases so slowly that it may be years before it’s a visually wonderful match with shallow-rooted, ground floor sedum ‘Vera Jameson,’ but that day is almost sure to come.

However, when the paired plants are both vigorous growers, it’s best during the wait and see period to adopt the laissez-faire of a really good kindergarten teacher. Watch and tolerate rambunctious individuals so they have leeway to grow, and step in only when one’s assertiveness becomes a threat to another’s growth. Stepping in between plants may involve judicious cutting back during the season, yearly thinning, or staking the lark to allow the owl to emerge with straight stems.

Consider once more the oriental poppy/hardy hibiscus double up. Through a wait-and-see strategy, I learned that a slow-growing pink cultivar of oriental poppy may coexist peacefully with hibiscus, but the rampant red-orange standard doesn’t play nice and will abuse a well-mannered partner if I turn my back. One year, I planted both types of poppy, each with a hibiscus companion. The pink poppy and its hibiscus are still happy campers seven years later, without any interference from me. The red-orange beast, however, acts like a red tide and would reduce its hibiscus partner to a tired swimmer trying to keep her nose up to that crimson surface, except that I act as referee.

So I wade into my red-orange poppy every June as the flower petals fall to remove that foliage before its time. I grasp each cluster of poppy leaves and stalks, then give a sharp tug to break it off below soil level. I learned that this does not kill the poppy, just slows its spread. It does free the emerging hibiscus shoots from the poppy’s shade. I can almost hear the hibiscus gulp in air as I pull the poppy out of the way.

Accommodate the staggered start.

Some pairings involve plants that are best planted in a certain season—bulbs in fall, the first sowing of a self-seeding annual in spring. Yet you may want to plant their double up counterpart earlier or later. Or you may decide to try doubling up beginning with an established plant in your garden. The challenge is to insert the second plant and insure its good start but cause minimal disturbance to the first.

It can be a puzzle to do this with bulbs, especially the big ones. The plants they double so well with are often in full, glorious bloom at bulb-planting time. Perhaps tiny bulbs can be shoehorned in with a narrow trowel, but the gardener can’t bear to insert a spade and ruin that show. The best answer I’ve found is to wait until November to add the bulbs. Then the new additions still have time to get established before their debut, yet I’m less hesitant to plant in the other plant’s midst.

The reverse of that situation, planting an owl companion in spring among already established larks, is also difficult. Digging to place a one-gallon container of Japanese anemone among bulbs is likely to destroy or at least set the bulbs way back. When working among spring bloomers, it’s more do-able to trowel in several three-inch pots, small divisions of a late riser perennial, or the smallest available cell packs of an annual, or simply sow seeds between the established plants.

Sometimes you do have space at ground level for digging, but the air space is full of stems of established plants. You have to be a terrific lightfoot to avoid bending or snapping stalks as you work in that already tight place. I find elastic tarp straps helpful for cinching in existing plants, temporarily reducing their girth while I plant between them.

Have fun but don’t go broke!

Which brings me to one final, practical aspect of doubling up—the cost. It’s more costly than conventional planting because you plant two for one and there is always the chance that a pairing will fail. That consideration, along with the knowledge that small plugs make better double ups, keeps me always on the look-out for small starts at garden centers and plants that can be divided to plant as double ups. You can also do some begging of perennial divisions from fellow gardeners. Since you’ll request only very small divisions, perhaps your friends will be more likely to say yes. Then you can cut your costs even as you double your perennial show!

Article by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.