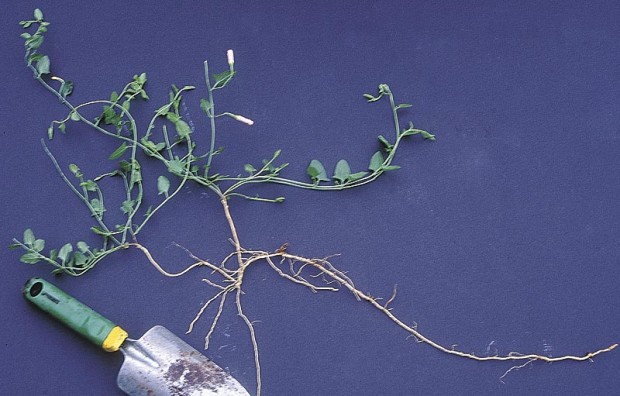

One “star” of this article is evident here to the trained eye.

By Janet Macunovich / Photos by Steven Nikkila

Why are weeds so hard to talk about?

We spend much of our in-garden time preventing and removing weeds. Perhaps you haven’t counted those hours, but I have, since I garden professionally and must account for my time. Bottom line? We spend 30 to 35 percent of our gardening hours in pursuit and defiance of weeds.

The books, magazines, TV shows and newspaper articles into which we pour our disposable incomes don’t seem to recognize this. Twenty magazines pulled at random from my current stash yielded 220 article titles. If topics were chosen commensurate with the attention we give a subject in our gardens, about 70 of those articles should have been weed-oriented. Yet only three titles even included the word “weed.”

Should the weed-disabled gardener hit the books? I tried it, searching in general gardening encyclopedias. An “Illustrated Guide to Gardening” was typical in its coverage, allotting just ten of its 649 pages to “Weeds and Their Control.”

Weed books do exist for those who hunt. My collection, built slowly over twenty years, consists mostly of textbooks and publications from various agricultural universities’ Extension services. Although there is plenty of useful information in “Problem Perennial Weeds of Michigan” (Michigan State University Extension bulletin E-791) and in “Weeds” (a textbook published by Cornell University Press), it’s dry, dry, dry.

Worse, the suggested control methods in textbooks and Extension bulletins are mostly geared toward agricultural and commercial users. “Repeated mowing,” “clean cultivation” or “fallowing for one season” might be practical for a farmer, but are tough to translate to the home garden. Likewise, a professional landscaper may benefit from the advice “timely spot treatment with the proper herbicide,” but most of us don’t care to know which of the many herbicides available only to professionals would work even if we could buy them because it’s not often practical to apply herbicides in established beds.

three-year battle. It’s also known as wild morning glory, for its trumpet-like flowers, white aging to pink (here closed on a cloudy day).

So let’s get down and dirty. First, that means we start looking at and talking about weeds without shame. They’re an integral part of gardening, so let’s accept that and acknowledge they’ll always be with us. Stop disguising them under mulch, apologizing for them, or diverting visitors from beds where they dwell. Quit refusing to admit you’re growing any. Or many. This attitude adjustment can take time but it’s the ultimate liberation. It’s the perspective that allows me to smile as I write, “Every weed in this article and in these pictures is my weed. I grew it!”

The more we bring weeding out from under the carpet, the more we can draw on each other’s experience and help. Just think how far ahead we’d be if we shared even a tenth of the tips on weed-beating that we share on rose-growing. Talking more means we’ll also begin to look more closely at our weeds and know them better.

What a wealth of information becomes available when you have a weed’s name. Look it up in the dictionary, check for it in a weed textbook, ask about it at the Extension, type its name into an Internet search engine. In knowledge is power—in this case, power to predict, undermine and eliminate.

To identify your foes, start with MSU Extension weed bulletins—several include color photos. No luck there? Flip through weed textbooks at a library. Still nameless? Press a sample of the weed, preferably with root and flower or seed pod intact, sandwich it between sections of newspaper and stack heavy weights on it for a week. Tape the flattened sample onto cardboard and take it to garden centers, garden club meetings and plant swaps. Someone will give you the name.

Even before you know your pest’s proper name you can start working on the next most important fact—is it a perennial, annual or biennial? Many perennials reveal their long-lived nature through their roots. Loosen the soil all around the weed and remove it carefully, roots intact. Look for underground runners that pop up into new plants, or bulges and knobs on a horizontal root that foretell new shoots. The presence of storage organs such as bulbs and tubers are also telltales that the plant’s either perennial or biennial. There’s no other reason for a plant to store away a lot of starch except that it’s planning to come back next year.

Which brings me to another “must-do” when it comes to weeds. That’s to stop looking for miracle techniques and products. Weeds caught early on, under two inches tall, can be dispatched fairly easily with a hoe or a smothering mulch. Give them a year and you’re in for a battle that requires a discriminating eye and lots of hand work.

I’m not saying I like this fact. Established perennial weeds make me cringe. That’s what’s wrong with the lead picture in this story. See that Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) among the hostas on the left? Okay, go after it. Loosen the soil, remove every bit of root you can find. Then acknowledge the root’s depth, brittleness and tenacity by returning every week or ten days for two whole seasons, April through November, to nip off every bit of thistle that tries to make a comeback. At the end of the second year, you may have starved it out—forced it to exhaust all the reserve starch in its roots.

Perennials and biennials can stash an amazing amount of starch in their roots, given even a bit of green leaf to work from. Take a carrot (Daucus carota) in its weed form: Queen Anne’s lace. It’s as cute and small as a carrot-top in its first year – just a bunch of low, feathery leaves. Yet look what the root produced by those leaves delivers in year two—four feet of stately stem, leaf, flowers and thousands of seeds. No wonder when we leave a bit of weed root in the ground, it manages to keep sprouting for years.

Bindweed (Convulvulus arvensis) is worse. Given time to establish, its roots may dive 15 feet deep. If dug well and then nipped in the bud every six days—more frequently when the growing is good—it takes 2 to 3 years to wear it out.

Don’t confuse hedge bindweed (Polygonum convulvulus, also called wild buckwheat) with perennial bindweed. An annual, wild buckwheat is far less trouble to beat—just keep it from going to seed. That means where blown-in seed or seed-infested mulch spawns an invasion, weed thoroughly several times before mid-June.

Scouring rush or field horsetail (Equisetum arvense) drives people crazy yet it’s a wimp compared to bindweed and Canada thistle. Dig it well, focusing on those enlarged tuber roots, keep new shoots nipped weekly for one season and it’s gone.

Tuber roots are what make yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) such a scourge. Pull on this weak-looking, creased-blade grassy creature and it comes readily, with what looks like all roots intact. Those in the know, however, understand that if you don’t get the nut out, you don’t get the sedge out.

Yellow wood sorrel (Oxalis florida) is another perennial that fools us by pulling easily and seeming to have little root. That’s because its running roots break loose and stay behind when we pull—a good reason to study the plant, learn that it has runners and loosen the soil well throughout the area before pulling.

Obviously, we can’t cover all weeds and weeding techniques in this article, but this is a good start!

Janet Macunovich is a professional gardener and author of the books “Designing Your Gardens and Landscape” and “Caring for Perennials.” Read more from Janet on her website www.gardenatoz.com.