Here we are at the garden center, wrestling once again with that essential question: When picking a size, is it better to pay more, for immediate satisfaction, by buying the largest specimen? Or is a smaller plant the wiser investment?

The answer is a classic: It depends. But current research is providing objective, specific and sometimes surprising information that may weigh in your decision.

General buying guideline: Roots rule and water pays the bills

No matter what plant you’re buying, choose the package that delivers more roots in a wider formation, and plan to water attentively until the plant resumes growing as well as it did in its production field.

All plant parts begin as soft growth—as leaf, shoot or root tip. 95 percent of that growth is water, which enters the equation as a puddle sinking into the soil, pushing into soft root tips and being drawn up by photosynthesis to the leafy part of the plant. The winner in any growing contest will be the plant with enough roots to serve its whole top, spread to cover a wider surface that “catches” a bigger puddle.

Roots develop only when leaves produce more sugar and starch—energy—than they need to sustain themselves and woody parts nearby. As the root system expands, more water can enter a plant, which can then support more leaves. So leaves and roots grow in balance, equal in mass and in width of spread.

When a plant must be dug from one place to be planted in another, root loss is inevitable. When the plant is grown in a container that prevents roots from spreading as wide as the branches, it can’t make use of natural, wide puddles but becomes reliant on a near-constant flow of water through its small area of ground, via frequent watering or trickle irrigation.

It may be a year or more before a transplant’s leaves manufacture significant spare energy and roots begin to recoup their loss. As long as the roots remain “behind,” the plant will grow fewer new leaves each spring than it should. In such a year, total root growth can’t measure up to potential, either. A few or many years can pass during which the top remains the same size or even shrinks and the roots slowly increase, until balance and normal growth resumes.

Trees: Smaller is often better

When instant gratification is an operative factor, you can’t persuade yourself or anyone else to buy small. But if you think putting a larger tree in the ground is a jump start toward a shaded yard or the glory of a full-sized ornamental tree, think again. Small trees often catch up to larger trees planted at the same time and may keep growing faster for decades.

Tree roots grow out, not down. So to stay balanced in mass and spread with the top, they spread wider than the branches. Even small trees have wide root systems. If a conventional pot or root ball was cut wide enough to encompass all of a substantial tree’s roots, it would be an unmanageable package for grower, garden center employee and you. Thus all trees sold at a garden center are unbalanced with the possible exception of bare root trees, seedlings or “whips,” and those grown in the unfortunately-uncommon flat-pan method.

The larger the top of the tree, the more out of balance its for-sale root ball. So the largest trees take the longest to regain balance and resume growth.

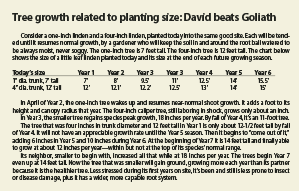

We buy trees rated according to their trunk diameter: “one-inch caliper,” “two-inch caliper,” etc. Studies show there is a direct relationship between this trunk size and root re-establishment time. For every inch in trunk diameter, a properly-sited, well-watered tree will take at least one year and possibly longer to recoup its losses. Smaller trees recover faster than larger trees—one year for a one-inch tree, five years or more for a four-inch tree.

That means a one-inch tree may shake off its shock and resume growing roots at a normal rate even during its transplant year. For most tree species, it’s normal to lengthen each root about 18 inches during a typical, zone 4-5 growing season. With that much new root, the tree is able to produce leaves and extend its branches to full potential the following spring—18 inches or more for fast-growing species like silver maple or river birch, 12 to 18 inches for moderate growers such as red oak and katsura, and 6 to 12 inches for slow-growing American hornbeam or bur oak.

Meanwhile, a four-inch caliper tree will take five years to return to this norm. It may extend its roots and its branches only an inch or two in year one, and continue to creep in growth over the next four years.

Exception: In seedling trees, pick the largest

So where you want one or a few trees, the fastest possible growth, shortest term of critical care and healthiest trees in the long run, buy small rather than large.

However, if your aim is to replant a forest or start your own grove of trees, seedlings or unbranched young trees called “whips” are usually the way to go. In that case, bigger is better. Given a choice of many whips, choose those which are thickest at their stem base. If all have the same size stem base but some are taller, choose the taller.

Pacific Regeneration Technologies, a network of reforestation nurseries in Canada and the U.S., has compared survival and growth rates of smaller and larger seedlings in the field. Although there are many variables that can affect these plantings, PRT’s findings are persuasive—thicker and taller seedlings have higher survival and growth rates. In one study of Douglas fir, the differences in survival and height remained almost unchanged even 21 years after planting.

Shrubs: Hedging changes the bet

Shrubs and trees are the same in many ways, including best planting size. The wider the roots and the closer they are to being balanced with the top, the more quickly that shrub will “take” and the better its long-term prospects.

Shrubs to be used as hedging are exceptions. Smaller shrubs, even seedlings, almost always outgrow larger plants when planted in close rows. A hedge begun with smaller plants is ultimately fuller, healthier and requires less care. Even most important, the hedge grown from seedlings or small shrubs is less likely to suffer middle-of-the-row losses as it ages.

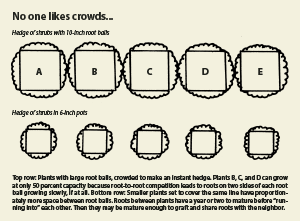

Competition for water is why large-plant hedges fall short in speed and fullness, compared to hedges begun with smaller plants. Larger plants have larger root balls and once planted, each one has proportionately less root-growing space.

When roots are in direct competition with other roots, they grow slowly, if at all. It makes no difference that competing roots are from a related plant and the two sets of roots, if growing vigorously, could graft and become a single system. A line of large plants with root balls tucked one against the next is a line of plants with only half its roots free to grow. At best, those plants can grow at half capacity.

In addition, smaller plants have been sheared fewer times, so they’re less dense and cast less shade on other plants’ bases. A hedge grown from whips becomes and remains full at the bottom. Larger shrubs, pruned repeatedly for fullness before being sold to the hedge planter, thin out at the base and rarely regain density as they grow together.

A hedge that began with crowded roots remains weak. The weakest individuals are in the center, where competition was most fierce, side roots atrophied and each plant’s root mass remained small. Years and even decades later the hedge crowded at planting is most likely to be affected by drought, severe winters or seasons of high insect or disease occurrence. The plant in that hedge most likely to die is one in the middle.

Perennials: Buy what you can afford, but give them rooting space

Trees, shrubs, vines and bulbs are perennials, as are those plants in the group most commonly called perennial—herbaceous flowering species from anemone to zebra grass. I hope you’ll keep in mind that every perennial is alike in a way that should influence your choice in plant size. That is, they all store energy this year for next year’s growth.

So buy perennials for the roots. Select the biggest, widest root system.

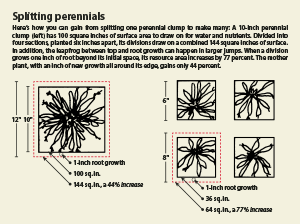

As far as the roots spread by the fall of one year, that’s as much area as the plant’s top will cover the following year. So do everything you can to encourage roots to spread during their first year.

If you buy perennials of any type for immediate impact, you will probably also plant them close together. That’s fine, if this year’s show is all that counts. However, to make the most of those plants over the long run, understand that crowded roots won’t grow as much this year as they could, so next year’s top growth will be less and plants will be weaker overall. If you must crowd for immediate show, enjoy the display then dig and replant the component parts farther apart.

To cover the most ground for the least money, buy smaller perennials. (But not too small—see the notes about annuals and vegetables, below.) If the plant you want is available only in large pots, buy those and divide them as you plant.

Annuals and vegetables: Pay-off’s in the larger cell

For healthy, lush annuals and vegetables, space them as directed. That is, if the pot tag says “space plants 12 inches apart,” give every one its own square foot. A flat of 48 plants can cover 48 square feet—a 4-foot by 12-foot bed.

Want a more spectacular show, sooner? Do what botanical gardens do—keep the spacing the same but start with bigger plants. The higher cost per square foot pays off in immediate display.

Since most studies are on vegetables, we need to apply that data to annuals—there are enough parallels to make the comparison worthwhile. For instance, vegetables that flower earlier go to market sooner. Those that are healthier bear larger fruit and have fewer pests, so more of the fruit is cosmetically perfect and sells for a higher price. We value early flowering and health in bedding plants, too.

Trials run in Michigan, Kentucky, Missouri, Georgia and Minnesota on tomatoes, broccoli, cabbage, pepper and watermelon planted from various size cells, showed that the largest transplants yielded earlier and/or more. From larger sets the first picking of tomatoes and peppers was up to twice as great. The broccoli crop was 25 percent more, cabbages 16 percent heavier and watermelon harvest 7 percent higher. We flower growers may not be big on math, but we can still see that sometimes it can be worth spending 50 percent more for the chance at doubling the show!

Parting shot: Small plants more foolproof

Still not sure what to do? In such cases, I buy small. It pays off, especially when I’m not sure what the plant can do or where it will grow best.

Big, bushy plants can fool me by looking big and bushy even as they lose ground—who notices ten leaves gone when there were 200 to start?

A plant that comes to me with just ten leaves tells me clearly, week by week, how things are going. If it’s thriving, its leaf count increases and the new foliage matches the old in size and color. If it begins to lose ground, that’s also quickly apparent. If it seems a move is in order to correct the situation, that’s simpler with a small plant too!

Article and illustrations by Janet Macunovich and photos by Steven Nikkila, www.gardenatoz.com.

ALSO… How Much are the trees in your yard worth?

ELSEWHERE: Planting a tree successfully requires the correct planting depth

David Torgoff says

Excellent article in every way.

Thank you!

jhofley says

Thank you for reading, David!

Lesli says

Very helpful–thank you!