by Christine Jamieson

The film Master and Commander brilliantly recreated life on an 18th century man-of-war. One of the most thrilling episodes is where the ship visits the Galapagos Islands and the ship’s doctor attempts to collect plant specimens and then later draws them. This is an authentic depiction of voyages in those days.

Shortly before the onset of the war depicted in the film, Captain James Cook had made his famous voyage around the world. Financed by the immensely wealthy and exuberant Joseph Banks, there were two botanical illustrators on board, Alexander Buchan and Sydney Parkinson, who recorded in great detail the strange flora of Australia, New Zealand and Tahiti. Parkinson died before reaching England again, but his work lives on in some 700 paintings in Banks’ Florilegium, which was finally published in full color in the 1980s. Banks went on to found Kew Gardens, making it one of the world’s greatest herbariums and botanical gardens.

Another sailor, William Roxburgh from Scotland, enlisted as surgeon’s mate on a ship bound for India in 1786 when he was only 17. There he became so interested in the indigenous vegetation that he abandoned medicine in favor of botany and eventually ended up as curator of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens.

This was the age of scientific inquiry when men (and later some women), mostly from Western Europe and England, journeyed to North and South America, Russia, and the Middle and Far East in search of plants. In 1712, English botanist Mark Catesby traveled to America as the first professional plant collector. Not only was he a consummate naturalist but his drawing skills were also outstanding. As a result of his travels he published his Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, filled with wonderful illustrations.

Up until this time the Americans, busy as they were with settling the land, cultivating crops and generally struggling to survive, had not produced a homegrown botanist. However, John Bartram, a Quaker born in Philadelphia, had an astonishing career. Not only did he send more specimens to Linnaeus for classification than any other plant collector, he also supplied the English aristocracy with plants and set aside five acres on his farm as a botanical garden. Not an illustrator as such, he nevertheless made a huge contribution to American horticulture along with André Michaux and Thomas Nuttall, who published A Genera of North American Plants in 1818.

Almost since the world began there has been an interest in plants and in depicting them, from the time of the Egyptians, to the Chinese, Greeks and notably the Dutch with their wonderful still lifes of flowers and fruit as well as lovely paintings of single tulips. But it was in the 19th century that botanical illustration for its own sake, rather than for scientific advancement or medical knowledge, became a craze. There still were books devoted to the medicinal qualities of plants, but it was the diversity of exotics from far flung places that appealed to the public. When pictures of the first peonies were exhibited they caused a sensation!

Before my artist friend turned to glorious abstracts, she was a botanical illustrator. “Ligularia ‘Desdemona’?” I exclaimed immediately upon seeing one of her delicate paintings, not only botanically accurate but innately lovely. The essence of this type of art combines accuracy with beauty and was one of the most fashionable ways of painting in the 19th century.

In 1797, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine became the first periodical devoted exclusively to plants, followed by other significant publications like The Botanist, The Gardener’s Magazine and Horticultural Register. Because there was so much competition, the standard of illustration was very high. It seemed that people could not get enough of flowers. Following the botanical magazines came books devoted to the language of flowers and books describing how to draw them.

Nor was the United States immune from plant mania and the best known magazine here was A. J. Downing’s The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Taste which later merged with the Gardener’s Monthly.

One of the great illustrators was Jane Webb Loudon, who was a competent gardener as well as an artist, and published paintings of both garden and hothouse flowers in The Ladies Flower-Garden. The Belgian, Pierre Joseph Redoute, is remembered for his exquisite paintings of roses from the gardens of Malmaison, which were the pride and joy of Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife, the Empress Josephine.

Then there was Elizabeth Blackwell, whose husband Dr. Alexander Blackwell opened a print shop in London before he had completed his apprenticeship. As this was illegal he was arrested and imprisoned. Wondering how on earth she could help him and beside herself with anxiety, she heard that some local doctors needed an illustrated herbal guide. Elizabeth started work near the Chelsea Physic garden studying and sketching plants. She knew that as a woman it would be very difficult for her to get help to produce her book, so she decided to engrave her drawings on copperplate, and hand color them herself—a huge undertaking. Eventually she published a magnificent work, A Curious Herbal and made enough money to get her husband out of debtors’ prison. However, some are born to trouble as the old saying goes and no sooner was he released than he traveled to Sweden where he became involved in a conspiracy to change the Swedish succession! For this he was executed in 1747. Elizabeth never did any more illustrations and died 11 years later.

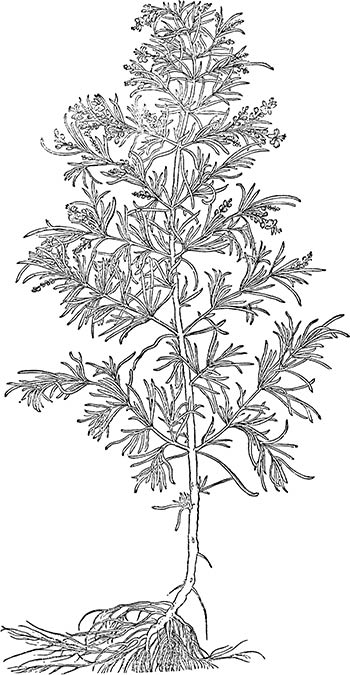

She was following a very early tradition of botanical drawing for medical purposes, which came long before both scientific exploration and cultural expression. For several thousands of years the Chinese were engaged in extensive medical botany and the Roman Pliny included botany in his Naturalis Historia. But it was a 1st century Greek physican, Dioscorides, whose work De Materia Medica was the definitive text for 15 centuries. According to one expert, its illustrations “display a standard of excellence in plant drawing that was not to be surpassed for almost a thousand years.”

Botanical art is still considered a valuable adjunct to photographs in horticultural academia. What about having a go yourself? Perhaps your botanical drawings could become the next best seller!

Christine Jamieson is a Michigan gardener and writer.

Leave a Reply