by Janet Macunovich / Photos by Steven Nikkila

In July it can be oppressively humid. As the heat takes its toll and frustration sets in, let’s look at some common summer garden problems.

Holes in hostas are history.

Most of the damage you see in July took place months ago when that foliage was cool and new. As bad as your hostas may look, the condition is far from fatal. The plants have had plenty of time in the sun to photosynthesize all the sugars and starches they need for the year plus sock away the surplus for next spring. In between holes, they still have lots of leaf surface left to keep on banking starches right into fall.

Whatever you do, don’t put out little saucers of beer now, even though it’s true that they will attract and drown slugs. The time to deal with that slug problem is next spring. Then, clear away all the mulch and other plant debris from slug-riddled areas. Leave the soil surface naked and dry. While hostas and other plants are emerging, during the last half of April and first half of May, set out slug traps. Beer traps are fine, but wetted sections of newspaper are at least as good, and they’re far less messy. Just lay them down in the morning near the first hosta shoots, then flip them over before the sun goes down and kill the slugs you find hiding there. They hide there because you took away all the other places where they might have escaped the sun. Dispatching a hundred slugs in April is more productive and far less smelly than drowning a thousand in July.

What goes down will come back up.

Eye-cooling lobelia, pansies, verbena and some other annuals have the habit of opening one last flower on the fourth of July then stretching out to give dirty sweat socks a run for the “Most Ugly” title. They can be made a bit neater in July but will rarely resume blooming until mid- or late August. That’s because it’s too hot at night. So chemicals that would be created within the plant’s cells while it’s cool and dark don’t form. Those chemicals provide the only nudge that can make the plant produce new flowers. Without their chemical cues, the plants sit out July—green, seedy and waiting.

Cut back your heat-stalled annuals now. They’ll grow back over the next month and resume blooming shortly after the heat breaks in August. The first aim of cutting back is to eliminate all the seed pods that are developing—as seed forms, it delays formation of new blooms. The shearing also stimulates new, bushier growth. You can clip so far as to leave only a few inches of stem. Keep the plants well-watered and apply a half strength, water-soluble fertilize after a couple of weeks. Be careful not to overdo the water or fertilizer for plants in a container. Once cut back they have less leaf surface to take up water. They may need less frequent watering than they did in spring since they’re taking longer to use what the pot can hold.

Just close your eyes and smell.

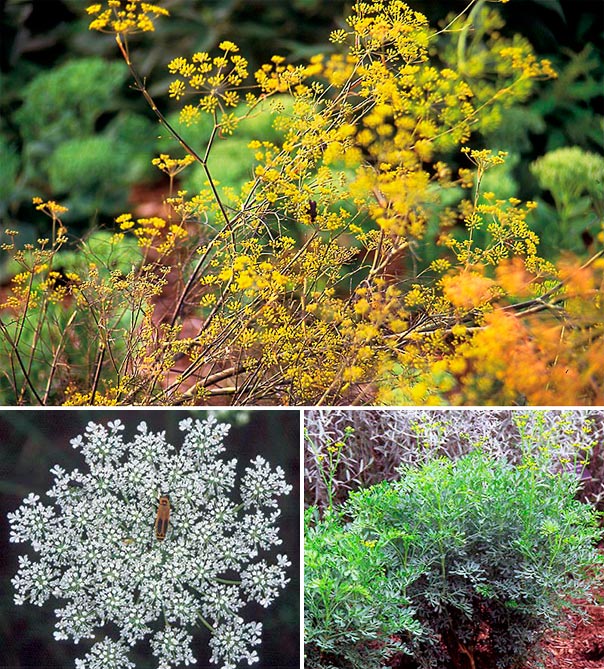

Powdery mildew annoys people out of all proportion to the damage it does to plants. In spring, one kind of mildew fungus or another can and usually does infect the leaves of tall phlox, bee balm, aster, zinnia, perennial sunflower and some other garden plants. During the cool weather the fungi grow slowly within the leaves, which continue to function normally if less vigorously. Then when conditions are right, the fungus finishes its development and covers the leaf with gray spores.

By the time we see gray, the damage is already done. You can try to arrest the mildew’s spread by plucking off all discolored leaves and spraying a fungicide on those that look healthy. Or you can sit back, close your eyes and smell—those sweet-smelling flowers still come, using energy captured by the leaves over more than three months.

Spraying can add fuel to the July fires, though. Whether it’s a purchased fungicide or one made with the baking soda on the kitchen shelf, applying it always carries some risk of burning the crabapple foliage or the leaves of sensitive plants nearby. The chances of causing a chemical burn are much higher when the air is hot and the plant is stressed by drought or heat—July conditions.

Don’t run up a tab for a scabby crab.

Crabapple scab is a fungus that acts much like powdery mildew, infecting early and showing itself late. It’s not unusual for a crabapple that’s susceptible to apple scab to defoliate by August. Its leaves yellow and drop off one by one as the fungus finishes its work. Once again, this is disfiguring but not a threat to the crabapple’s existence. Given an observant resident gardener as a guide, you can find at least one full-sized, regularly-blooming crabapple in every neighborhood that has dropped its leaves early every year for 30 years or more. Even if July’s pressure makes you feel you must do something for a scabby crabapple, all you should do at this point is rake up the diseased foliage and cart it away.

Then, if you still feel anxious about your crabapple next March, you can call a tree care company and sign up to have the tree treated several times with a scab-preventive fungicide, beginning when the leaves first begin to grow. Don’t try it yourself—most home spray equipment is far too small and most crabapples are far too big to be an effective match.

Janet Macunovich is a professional gardener and author of the books “Designing Your Gardens and Landscape” and “Caring for Perennials.” Read more from Janet on her website www.gardenatoz.com.