After a moderate rain, water collects in a shallow ditch at the back of my lawn. It looks swampy every year. Any design/planting ideas to improve the look of this area?

This unfortunate nuisance that often occurs in both old and new landscapes is actually a garden opportunity. Evaluate the square footage involved and consider putting in a rain garden. Very simply, a rain garden is a planted depression that allows rainwater runoff from impervious urban areas like roofs, driveways, walkways, and compacted lawn areas the opportunity to be absorbed. It reduces rain runoff by allowing storm water to soak into the ground (as opposed to flowing into drains and surface waters, which causes erosion, water pollution and flooding).

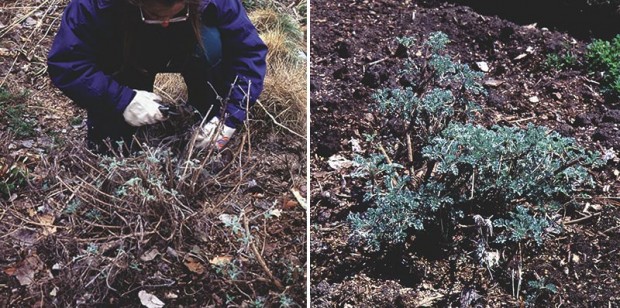

Usually, it is a small garden that is designed to withstand the extremes of moisture and concentrations of nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus often found in storm water runoff. A rain garden retards the water flow and absorption, allowing more time to infiltrate and less opportunity to gain momentum and erosive power. Because this area is in your lawn, you have the opportunity to prepare an area with select trees and shrubs as well as perennials that will enjoy absorbing and utilizing that rainwater, processing it, and creating an entire ecosystem beneficial to the greater good of the landscape.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has a 32-page online manual for the how-tos of constructing a rain garden, from measuring to digging to planting. They even include several design diagrams. The basic information is excellent, but it does focus on downspout and house foundation locations for the most part.

The key for an area like yours (away from a downspout) is to use tree and shrub species that love wet conditions. There are a number of Michigan native plants that suit the criteria well. Because you are not necessarily restricted by the proximity of a building, you can consider using trees like river birch (Betula nigra ‘Heritage’), which has the grace of a willow but none of the mess. It also has excellent winter interest in its buff pink, exfoliating bark.

Consider planting a cluster of red and yellow twig dogwood shrubs (Cornus sericea ‘Alba’ and Cornus sericea ‘Flaviramea’). These shrubs are especially suited to swampy areas and, with their colorful twigs exposed in Michigan winters, become a highlight of the snow-filled landscape. Depending on how large your ditch is, you could possibly add a smaller ornamental tree such as a native witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), which blooms in October and November, or a native shrub such as the common elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) whose fall fruit provides a great food source for both birds and animals.

Planting a rain garden is a very eco-friendly way to deal with standing water and provide assistance to the natural filtration process for our groundwater. You not only solve the drainage problem but also turn an eyesore into a work of beauty.